This is a work in progress. It is the first draft of a paper by Ludger Deitmer and myself for the Personal Learning Environments Conference to be held in Aveiro next week. We are looking at how we might develop work based PLEs drawing on the work on the forthcoming Learning Layers project. there is a downloadable version (in word format) at the bottom of the post. Your feedback is very welcome.

Developing Work based Personal Learning Environments in Small and Medium Enterprises

Graham Attwell, Pontydusgu, Wales

Ludger Deitmer, ITB, University of Bremen, Germany

Abstract

This paper is based on a literature review and interviews with employers and trainers in the north German building and construction trades. The work was undertaken in preparing a project application, Learning Layers, for the European Research Programme.

The paper looks at the development of High Performance Work Systems to support innovation in Small and Medium enterprises. It discusses the potential of Personal Learning environments to support informal and work based learning.

The paper goes on to look at the characteristics and organisation of the building and construction industry and at education and training in the sector.

It outlines an approach to developing the use of PLEs based on a series of layers to support informal interactions with people across enterprises, supports creation, maturing and interaction with learning materials as boundary objects and a layer that situates and scaffolds learning support into the physical workplace and captures people’s interactions with physical artefacts inviting them to share their experiences.

Keywords

Building, construction, Small and Medium Enterprises, informal interactions, boundary objects, workplace learning, scaffolding

1. Introduction

Research and development in Personal Learning Environments has made considerable progress in recent years. Yet although often acknowledging the importance of informal learning, such research continues to be largely focused on formal educational institutions from either higher or vocational training and education. Far less attention has been paid to work based and work integrated learning and still less to the particular context of learning at work in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) (Gustavsen, Nyhan, Ennals, 2007). Yet it could be argued that it is in just these contexts, where work can provide a rich learning environment and where there is growing need for continuing professional development to meet demands from new technology, new materials and changing work processes, that PLEs could have the greatest impact. A work environment in which the workers plan, control and validate their work tasks can both competitive and productive (Asheim 2007). It also requires that workers are able to make incremental and continuous improvements to work processes to develop better products and services. This in turn requires continuous learning. In contrast to predominant forms of continuous training based on activities outside the workplace, and in response to the perceived lack of take up of Technology Enhanced Learning in SMEs, we propose a dual approach, based on informal learning and the development of network and mobile technologies including Personal Learning Environments. This paper will describe an approach being developed for learning in SMEs, specifically in the building and construction industry in north Germany.

Our approach is based on the development of high performance work systems in industrial clusters of SMEs. In this context, individual learning leads to incremental innovation within enterprises. Personal Learning environments serve both to support individual learning and organisational learning through a bringing together of learning processes (and technology) and knowledge management within both individual SMEs and dispersed networks of SMEs in industrial clusters. Our approach is also based on linking informal and work based learning and practice and formal training.

The paper is based on literature research and on interviews with employers and trainers in the building and construction sector. This work was undertaken in preparation for a project called Learning Layers, to be undertaken through the European Commission Seventh Framework for Research and due to commence in November 2012.

In the paper we look at the ideas behind high performance work systems and industrial clusters before examining the nature and context of the building and construction industries and particularly of SMEs within the industrial cluster.

We develop a scenario of how PLEs might be used for learning and suggest necessary developments to be undertaken to facilitate the adaptation of such technologies for learning.

2. The challenge for knowledge and skills for the workforce

Many industries are undergoing a period of rapid change with the introduction of new technologies, new production concepts, work processes and materials. This is resulting in new quality requirements for products and processes which lead to an emergence of new skill requirements at all levels of personnel, including management, workers, technicians, apprentices and trainees. These changes can be described as a paradigmatic shift from traditional forms of production towards leaner, agile and flexible production based on high performance work systems (Toner 2011).

Leaner business organisations have less hierarchical layers and develop ‘close to production intelligence’ in order to be more flexible to change and to customer demands. The qualifications required of workers within such production or service environment are broader than in traditional workplaces reflecting a shift from functional skills towards multiskilling. Skilled workers require practical and theoretical knowledge in order to act competently in the planning, preparation, production and control of work and to coordinate with other departments in or outside the company.

Information and communication technologies – including both technologies for learning and for knowledge management – are required to allow more decentralised control to support just-in-time and flexible production and services. A key to flexibility and high productivity lies in the qualification profiles of the workforce and in the development of worker-oriented production technologies, which allow more flexible control in the production process.

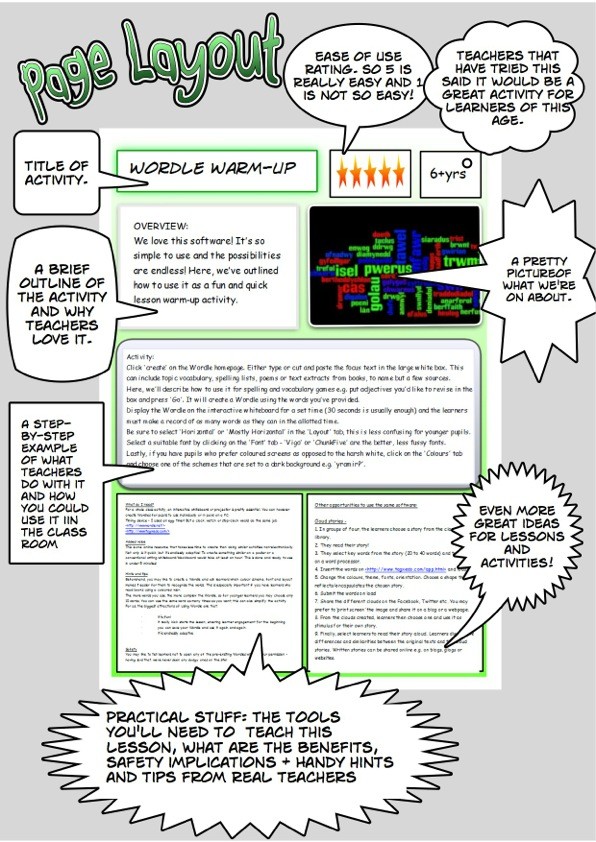

The following table illustrates the change in innovation management within such companies and the consequences for the skilling of workers, technicians and the apprentices. This change in production philosophy can be described as a move from a top-down management approach towards a participative management approach (Rauner, Rasmussen & Corbett, 1988; Deitmer & Attwell, 2000) which requires a commitment to innovation at all level of the workforce, not just at the management level.

| Innovation management by: control |

Innovation management by: participation |

Organisational consequences for the skilling of emerging workers |

| function-oriented work organisation |

business-oriented work organisations |

Learn to work within the flow of the business process and at the work place through experience-based learning |

| steep hierarchy |

flat hierarchy |

Self regulated working and learning based on methods like plan, do, act and control cycle |

| low level and fragmented qualifications |

shaping competences |

Be able to shape workplaces and make suggestions for improvement of services and production processes |

| executed work |

commitment, responsibility |

Developing vocational identity and occupational commitment |

| external quality control |

quality consciousness |

professional level of training based on key work and learning tasks |

Table 1 Innovation management and the skilling of workers (Deitmer 2011)

3. Learning by doing and drivers for incremental innovation

Toner (2011) points out that a ‘learning by doing’ strategy in an innovative work environment can lead to gradual improvement in the efficiency of the production processes and product design and performance (Toner 2011). Such improvements are based on high performance skills by workers. High Performance Work Structures are based on the practical knowledge of the workers underpinned by theoretical knowledge (Nyhan 2002, Rauner). Practical knowledge is generated in the context of application and is shaped by criteria such as practicability, functionality and the failure free use of technologies.

In high performance work systems (Toner 2011, Arundel 2006, Gospel 2007, Teece et.al 2000) the following qualification profiles are emerging:

- High levels of communication, numeracy, problem solving and team working are required as managerial authority is delegated to the shop floor including the design of the workplace, maintenance and continuous product and process innovation

- Broad Job Classifications which allow functional flexibility by limiting occupational demarcations and requiring workers to be competent across a broader range of tasks than is conventionally expected which in turn requires broad based training.

- Organisational learning around new patterns of activities is based on capturing the learning and work experiences of individual workers and teams of workers

- Flat management hierarchies provide more responsibility for individual workers and work teams in problem solving and in organising work processes

High Performance Work Systems require a commitment to innovation at all levels of the workforce; this process is more inclusive, democratic and incremental rather than elitist, imposed and radical. The empowerment of the work force to make proposals for changes and improvement is key. However the adoption of such practices requires continuous learning linked to knowledge management and systems and technologies to support such processes.

Thus the development of work based PLEs could be linked to wider processes of innovation within SMEs.

4. Learning and innovation in Regional Clusters

Many SMEs organise themselves in clusters or networks in order to collaborate, to share knowledge and skill, or even to exchange staff. The network dimension is particularly important as regional clusters have been understood as an instrument of scaling learning in heavily SME dependent sectors. This is reflected by large EU projects like European Cluster Excellence Initiative. It is much easier to economically justify the creation of learning materials which can be reused in an entire cluster and hence by many organisations than just for a few individuals. The challenge from a network point of view would be to identify such high potential learning materials and to find ways to distribute them efficiently within the network. The current focus of cluster initiatives is almost exclusively on scaling up formal training by organising training across network members. While a Communities of Practice perspective has been adopted in some cases to address informal learning processes, these are usually not effectively supported through information technologies (Prestkvern & Bardalen 2008).

Effects resulting from relationships in networks of small organisations for learning processes have received little attention in Technology Enhanced Learning research to date, despite these networks having been identified as a potential way of fostering favourable learning conditions (Deitmer & Attwell 2000). However, we can build here on work in diverse fields looking into these network effects. Seminal work by Granovetter (1973) has made distinction between strong and weak ties in such networks. Further studies investigated the network effects on experience sharing (Baum, 1998), on social networks (Cross, 2001), of trust on knowledge transfer (Levin, 2004) on communication for innovation (Müller-Prothmann, 2006), on communication with new media (Haythornthwaite, 2002) and more recently on networked learning (Ryberg, 2008). However, the effects on informal learning and on the creation of shared knowledge artefacts are still open issues.

The development and implementation of Personal Learning Environments within the context of regional clusters could support this form of networked informal learning.

However there remain barriers. Research suggests (Perifanou, forthcoming) that SMEs may still be concerned about a perceived loss of competitiveness through openness in collaborative learning contexts. Similarly some SMEs regard learning materials, especially those generated within their organisation, as a potential source of future revenue.

5. Learning approaches and technological support for learning at the workplace

Research suggests that in SMEs much learning takes place in the workplace and through work processes, is multi episodic, is often informal, is problem based and takes place on a just in time basis (Hart, 2011). Rather than a reliance on formal or designated trainers, much training and learning involves the passing on of skills and knowledge from skilled workers (Attwell and Baumgartl, 2009). Dehnbostel (2009) says that learning in the workplace is the oldest and most common method of vocational qualification, developing experience, motivation and social relations. Learning at work is self-directed, process-oriented form of lifelong learning that essentially contributes to personality development and professionalism, and promotes innovation and employability (Streumer, 2001; Dehnbostel, 2009; Fischer, Boreham and Nyhan, 2004).

A survey undertaken in Germany found work based learning comprised of 43% of training and learning undertaken by enterprises (Büchter et al., 2000).

Thus work based learning is seen as a potential approach to developing continuing learning for the broader competences and work process knowledge required for high performance workplaces. Rather than a reliance on formal or designated trainers, much training and learning involves the passing on of skills and knowledge from skilled workers (Attwell and Baumgartl, 2009). In other words, learning is highly individualized and heavily integrated with contextual work practices. While this form of delivery (learning from individual experience) is highly effective for the individual and has been shown to be intrinsically motivating by both the need to solve problems and by personal interest (Attwell, 2007; Hague & Lohan, 2009), it does not scale well: if individual experiences are not further taken up in systematic organisational learning practices, learning remains costly, fragmented and unsystematic. It has been suggested that Technology Enhanced Learning can overcome this problem of scaling and of systematisation of informal and work based learning. However its potential has not yet been fully realized and especially in many Small and Medium Enterprises (SME), the take-up has not been effective. A critical review of the way information technologies are being used for workplace learning (Kraiger, 2008) concludes that most solutions are targeted towards a learning model based on the idea of formal, direct instruction. TEL initiatives tend to be based upon a traditional business training model with modules, lectures and seminars transferred from face to face interactions to onscreen interactions, retaining the standard tutor/student relationship and the reliance on formal and to some extent standardized course material and curricula.

The development of work based Personal Learning Environments have the potential to link informal learning in the workplace to more formal training. Furthermore they could promote the sharing of experience and work practices and promote collaborative learning within networks of SMEs. Research suggests that in SMEs much learning not only takes place in the workplace and through work processes, but is multi episodic, is often informal, is problem based and takes place on a just in time basis (Hart, 2011).

Learning in the workplace draws on a multitude of existing ‘resources’ – many of which have not been designed for learning purposes (like colleagues, Internet, Intranet) (Kooken et al. 2007). Research on whether these experiential forms of learning lead to effective learning outcomes are mixed. Purely self-directed learning has been shown to be less effective than most guided learning in many laboratory studies and in educational settings (Mayer, 2004). On the other hand, explorative learning in work settings has often been reported to be beneficial, e.g. for allowing construction of mental models and improving transfer (Keith & Frese, 2005). Some form of guidance may be necessary to direct learners’ attention to relevant materials and support their learning (Bell & Kozlowsky, 2008). This is especially true for learners at initial levels (Lindstaedt et al. 2010).

One approach to this issue is to provide scaffolding. The use of scaffolding as a metaphor refers to the provision of temporary support for the completion of a task that a learner might otherwise be unable to achieve. Scaffolding extends the socio-cultural approach of Vygotsky. Vygotsky (1978) suggested that support for learning was provided by a Significantly Knowledgeable Other, who might be a teachers or trainer, but could also be a colleague or peer. Attwell has suggested that such support can be embodied in technology. However, scaffolding knowledge in different domains and in particular in domains that involve a relationship between knowledge and practice requires a closer approach to learning episodes and to the use of physical objects for learning within the workplace. Thus rather than seeing a PLE as a containers or connections- or even as a pedagogical approach – PLEs might be seen instead as a flexible process to scaffold individual and community learning and knowledge development.

6. Developing Work based PLEs in the Building and Construction Sector

In the first section of this paper we have looked at the idea of high performance work systems and innovation and knowledge development within industrial clusters. We have suggested that Personal Learning Environments could facilitate and develop these processes through building on informal learning in the workplace. We have recognized the necessity for support for learning through networked scaffolding. In the second section, we will examine in more depth the north German Building and Construction sector, developing a scenario of how PLEs might work in such a context. We will; go on to suggest further research which is needed to refine our idea of how to develop work based PLEs.

7. The Building and Construction Cluster

The building and construction trades are undergoing a period of rapid change with the introduction of green building techniques and materials and new work processes and standards. The EU directive makes near zero energy building mandatory by 2021 (European Parliament 2009). This is resulting in the development of new skill requirements for work on building sites.

The sector is characterized by a small number of large companies and a large number of SMEs in both general building and construction and in specialized craft trades. Building and construction projects require more interactive collaboration within as well as between different craft trade companies within the cluster.

Training for skilled workers has traditionally been provided through apprenticeships in most countries. Continuing training is becoming increasingly important for dealing with technological change. However further training programmes are often conducted outside the workplace with limited connection to real work projects and processes and there is often little transfer of learning. Costs are a constraint for building enterprises, especially SMEs, in providing off the job courses (Schulte and Spöttl, 2009). Although In Germany, as in some other European countries, there is a training levy for sharing training costs between enterprises, there remains a wider issues of how to share knowledge both within enterprises and between workers in different workplaces. Other issues include how to provide just in time training to meet new needs and how to link formal training with informal learning and work based practice in the different craft trades.

The developments of new processes and materials provide substantial challenges for the construction industry. Traditional educational and training methods are proving to be insufficient to meet the challenge of the rapid emergence of new skill and quality requirements (for example those related to green building techniques or building materials). This requires much faster involvement and action at three levels – individual, organisational and cluster. The increased rate of technical change introduces greater uncertainty for firms, which, in turn, demands an increased capacity for problem solving skills (Toner 2011). Despite the recession there is a shortage of skilled craftspeople in some European regions and a problem in recruiting young people for apprenticeships in higher skilled craft work in the building and construction industry.

In the present period of economic uncertainty, it is worth noting that the total turnover of the construction industry in 2010 (EU27) was 1186 billion Euros forming 9,7% of the GDP in 2010 (EU27). The construction industry is the biggest industrial employer in Europe with 13,9 million operatives making up 6,6% of the total employment in EU27 and if programmes were to be launched to stimulate economies, construction has a high multiplier effect.

8. Mobile technologies and work based Personal Learning Environments

Although the European Commission has pointed to the lack of take up of e-Learning in various sectors, this is probably too simplistic an analysis. It may be more that in all sectors, e-learning has been used to a greater or lesser extent for learning in particular occupations and for particular tasks. For example e-Learning is used for those professions which most use computers e.g. in the building and construction industries, by architects and engineers. Equally e-learning is used for generic competences such as learning foreign languages or accounting.

In the past few years, emerging technologies (such as mobile devices or social networks) have rapidly spread into all areas of our life. However, while employees in SMEs increasingly use these technologies for private purposes as well as for informal learning, enterprises have not in general recognized the personal use of technologies as effectively supporting informal learning. As a consequence, the use of these emerging technologies has not been systematically taken up as a sustainable learning strategy that is integrated with other forms of learning at the workplace.

9. An approach to developing PLEs in the work place

We are researching methods and technologies to scale-up informal learning support for PLEs so that it is cost-effective and sustainable, offers contextualised and meaningful support in the virtual and physical context of work practices. through the Learning Layers project we aim to:

- Ensure that peer production is unlocked: Barriers to participation need to be lowered, the massive reuse of existing materials has to be realized, and experiences people make in physical contexts needs to be included.

- Ensure individuals receive scaffolds to deal with the growing abundance: We need to research concepts of networked scaffolding and research the effectiveness of scaffolds across different contexts.

- Ensure shared meaning of work practices at individual, organisational and inter-organisational levels emerges from these interactions: We need to lower barriers for participation, allow emergence as a social negotiation process and knowledge maturing across institutional boundaries, and research the role of physical artefacts and context in this process.

10. The Learning Layers concept: an approach to support informal learning through PLEs

Work based Personal Learning Environments will be based on a series of Learning Layers. In building heavily on existing research on situated and contextualised learning, Learning Layers provide a meaningful learning context when people interact with people, digital and physical artefacts for their informal learning. Learning Layers provide a shared conceptual foundation independent of the personal tools people use for learning. Learning Layers can flexibly be switched on and off, to allow modular and flexible views of the abundance of existing resources in learning interactions. These views both restrict the perspective of the abundant opportunities and augment the learning experience through scaffolds for meaningful learning both in and across digital and physical interaction.

At the same time, Learning Layers invite processes of social contribution for peer production through providing views of existing digital resources and making it easy to capture and share physical interactions. Peer production then becomes a way to establish new and complementary views of existing materials and interactions.

Three Interaction Layers focus on interaction with three types of entities involved in informal learning:

- a layer that invites informal interactions with people across enterprises in the cluster, scaffolds workplace learning by drawing on networks of learners and keeps these interactions persistent so that they can be used in other contexts by other persons,

- a layer that supports creation, maturing and interaction with learning materials as boundary objects and guides this processes by tracking the quality and suitability of these materials for learning, and

- a layer that situates and scaffolds learning support into the physical workplace and captures people’s interactions with physical artefacts inviting them to share their experiences with them.

- All three interaction layers draw on a common Social Semantic Layer that ensures learning is embedded in a meaningful context. This layer captures and emerges the shared understanding in the community of learners by supporting the negotiation of meaning. To achieve this, the social semantic layer captures a number of models and lets the community evolve these models through PLEs in a social negotiation process.

The following scenario within the building and construction industry illustrate how these technologies will be operational in the regional North West German building and construction cluster.

11. Building and Construction Scenario: Cross-organisational Learning for Sustainable Construction

A regional training provider for the building industry offers courses on how to install PLC (programmable logic control) based lighting systems, a new technology designed for more efficient energy consumption. Veronika, a vocational trainer at a regional branch, designs a course on PLC based systems where she provides electronic materials. In the course, she distributes QR tags which participants can stick on devices in order to receive information on demand. She also integrates work-based exercises in her teaching where users tag PLC systems with QR tags, take pictures or create short videos, and add their personal experiences with these systems that they make available for other people as learning experiences [Artefact Interaction Layer].

Paul is a skilled electrician working in craft trade electrician service company who has not used PLC technology before. The PLC installation instructions are difficult to understand for him because he lacks experience with such installations. He scans the QR tag attached to the PLC with his tablet PC. The system suggests course materials from Veronika’s course, relevant standards for the installation from a technical publisher, as well as a short video documenting the installation steps recorded by a colleague [Artefact Interaction Layer]. Moreover, Paul receives the information that two people have experience with this particular PLC [Social Semantic Layer]. Paul calls one of them over Skype and checks that his plan and understanding of the installation is sound and then proceeds with the installation with the help of the video. As several further questions remain, Paul posts them using voice recording and photo to a Q&A tool [People Interaction Layer].

Paul’s question is forwarded to Dieter, an Electrical “Meister” in another SME using similar devices, based on his user profile indicating that he has experience with PLC, and because he has indicated his willingness to help. Dieter briefly answers Paul’s question, including links to materials (Pictures, …) available in the learning layers repository. Dieter is a well-known “problem solver” in his SME network. By support of the Learning Layers technology he has created a training business in which he gives technical advice service and trainings to other building electrician companies. His comments can be traced by others and recognized as service from the Electrician’s Guild.

Veronika, the vocational trainer, is notified by the system that there are currently many new activities around PLC programming and views the concrete questions that occurred [Social Semantic Layer]. With the notification, she also gets recommendations for the most active and helpful discussions and for most suitable and high quality materials people have suggested [Learning Materials Interaction Layer]. She decides to include these in her course to illustrate solutions to potential problems.

The four layers described in the previous section provide the core of the conceptual and technological approach for the development of the PLEs. There are two further critical elements that will be crucial for reaching our vision. These elements are needed for effectively integrating the different layers.

12. Further Research

Integration of work practices with learning to support situated, just-in time learning

We need further investigation into the relationship of informal learning and workplace practices on the individual, organisational and on the network level. In extending previous work, we will especially focus on physical workplaces and the opportunities and constraints that come with supporting learning. Secondly, we require a further focus on existing barriers and opportunities for scaling peer production and learning in cooperative-competitive SME networks. This work will create a model for scaling informal learning in a networked SME context and ensure that the use of tools is integrated through practice as suggested for example by Wenger, et al. (2009). But we generally acknowledge that a key factor for enterprises to staying agile and adaptive is to have a highly skilled workforce. With the rapid development of new technologies, staying up-to-date with know-how and skills increasingly becomes a challenge in many sectors.

Integration through a technical architecture for fast and flexible deployment:

Our idea is to base PLes on mobile devices, either the users’ personal devices or devices provided by the enterprises. However, the Learning Layers concept is based on fast and flexible deployment in a networked SME setting with heterogeneous infrastructural requirements and conditions. Current learning architectures are typically deployed as monolithic in-house installations that lack flexibility for inter-SME networking in response to fast-changing environments. On the other hand, externally hosted solutions are too restricted to features, devices and environments supported by the provider, again impeding flexibility and fast development cycles. Thus, the challenge of both fast and flexible development and deployment of learning solutions is currently not optimally catered for. This issue requires further research and development.

13. First Conclusions

This paper presents the early stages of research and development towards producing a system to support Personal Learning Environments in the workplace. There remains much work to do in realising our vision. We are attempting both to theoretically bring together approaches to innovation and knowledge management with learning and at the same time to develop pedagogical approaches to scaffolding learning in the workplace and develop technologies which can support the use of PLEs in networked organisational settings.

Our ambition is not merely to produce a proof of concept but to roll out a scalable system which can support learning in large scale networks of SMEs.

Our approach to developing the use of PLEs is based on a series of layers to support informal interactions with people across enterprises, supports creation, maturing and interaction with learning materials as boundary objects and a layer that situates and scaffolds learning support into the physical workplace and captures people’s interactions with physical artefacts inviting them to share their experiences.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the partners in the Learning Layers project application, on whose work this paper draws heavily.

Literature

Arundel A., Lorenz E., Lundvall B-A. and Valeyre A. (2006) The Organization of Work and Innovative Performance: A comparison of the EU-15, DRUID Working Paper No. 06-14

Asheim (2007), Learning and innovation in globalised economy: the role of learning regions In: Björn Gustavsen, Richard Ennals, Barry Nyhan (eds.) Learning together for local innovation: Promoting Learning Regions, Luxembourg: EUR-OP, Cedefop reference series; 68, pp 233

Attwell, G. (ed.) (2007). Searching, Lurking and the Zone of Proximal Development. E-Learning in Small and Medium Enterprises in Europe, Vol.5, Navreme Publications, Vienna

Attwell, G. & Baumgartl, B. (Eds.) (2009): Creating Learning Spaces: Training and Professional Development for Trainers. Vol.9, Navreme Publications, Vienna

Attwell, G.; Bacaria J.; Davoine, E.; Dillon, B.; Eastcott, M.; Fernandez-Ribas, A.; Floren, H.; Hofmaier, B.; James, C.; Moon, Y.-G.; Shapira, Ph.. (2002) State of the art of PPP and of evaluation of PPP in Germany, Greece, England, France, Sweden, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia and the US, ITB Forschungsberichte, Bremen

Kozlowski, S. and Bell, B. (2008). “Team learning, development, and adaptation.” Work group learning: Understanding, improving and assessing how groups learn in organizations: 15-44.

Braczyk, H.; Cooke, P.; Heidenreich, M.; (eds.) Regional Innovation Systems, London, UCL Press, 1998.

Büchter, Karin/Christe, Gerhard (2000), Qualifikationsdefizite in kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen?, in: Hoffmann, Thomas/Kohl, Heribert/Schreurs, Margarete (Hg.): Weiterbildung als kooperative Gestaltungsaufgabe. Handlungshilfen für Innovation und Beschäftigungsförderung in Unternehmen, Verwaltung und Organisationen. Neuwied, S. 69-80.

Camagni, R. (ed.). Innovation Networks: Spatial Perspectives. London, New York: Belhaven, 1991.

Cross, R., Parker, A., Prusak, L., & Borgatti, S. P. (2001). Knowing What We Know: Supporting Knowledge Creation and Sharing in Social Networks. Organizational Dynamics, 30(2), 100-120.

Dehnbostel, Peter (2009). Shaping Learning Environments In: Felix Rauner, Rupert MacLean International Handbook of Technical and Vocational Education and Training Research. Springer: Doordrecht, pp 531 – 536

Deitmer, Ludger (2011) Building up of innovative capabilities of workers. In: fostering enterprise: the innovation and skills nexus — research readings, ed.: Penelope Curtin, NCVER: National Centre Vocational Education Research, Adelaide

Deitmer, L & Heinemann, L. (2009), ‘Evaluation approaches for workplace learning partnerships in VET: how to investigate the learning dimension?’, In: Towards integration of work and learning: strategies for connectivity and transformation, eds. Marja-Leena Stenström & Päivi Tynjälä, Springer International, Doordrecht.

Deitmer, L. (2007), Making regional networks more effective through self-evaluation. In: Björn Gustavsen, Richard Ennals, Barry Nyhan (eds.) Learning together for local innovation: Promoting Learning Regions, Luxembourg: EUR-OP, Cedefop reference series; 68, pp 139-150

Deitmer, L., Gerds, P. (2002), Developing a regional dialogue on VET and training, in: Kämaräinen, P., Attwell, G.. and Brown, A. (eds.) Transformation of learning in education and training. Key qualifications revisited. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, European Centre for the development of Vocational Training, Cedefop. Luxemburg.

Deitmer, L.; Attwell, G.(2000): Partnership and Networks: a Dynamic Approach to Learning in Regions. Nyhan, B.; Attwell, G.; Deitmer, L., (eds.) Towards the Learning Region. Education and Regional Innovation in the European Union and the United States, CEDEFOP, Thessaloniki. S. 61-70.

Dittrich, J., Deitmer, L. (2003) The challenges in Teaching about Intelligent Building Technology. The Journal of Technology Studies. Vol 29, No. 2

European Parliament (2009) Announcement of European Commission on workplace learning. EU Communications 933/3 (cited from UK National Apprenticeship Service, Richard Marsh speach, 02/2012, Apprenticeship Week, London.

Boreham, N., Samurçay, R., & Fischer, M. (eds) (2002) Work Process Knowledge, Routledge: London

Floren, H. Hofmaier, B. (2003), Investigating Swedish project networks in the area of workplace development and health promotion by an support and evaluation approach. Halmstad: School of Business and Engineering,.

Gospel (2007), High Performance Work Systems, unpublished manuscript prepared for the International Labour Office, Geneva

Granovetter, M. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Gustavsen, Nyhan, Ennals (2007) In: Björn Gustavsen, Richard Ennals, Barry Nyhan (eds.) Learning together for local innovation: Promoting Learning Regions, Luxembourg: EUR-OP, Cedefop reference series; 68, pp 235-256

Hague, C., & Logan, A. (2009). A review of the current landscape of adult informal learning using digital Technologies. General educators report,futurelab.org.uk. Retrieved Jan 16, 2011 underhttp://preview.futurelab.org.uk/resources/documents/project_reports/becta/Adult_Informal_Learning_educators_report.pdf

Hart, J. (2011) Learning is more than Social Learning, http://www.elearningcouncil.com/content/social–media–learning–more–social–learning–jane–hart, retrieved 5 July, 2012

Haythornthwaite, C. (2002). Strong, Weak, and Latent Ties and the Impact of New Media. The Information Society 18(5), 385-401.

Kooken, J., Ley, T., & de Hoog, R. (2007). How Do People Learn at the Workplace? Investigating Four Workplace Learning Assumptions. In E. Duval, R. Klamma, & M. Wolpers (Eds.), Creating New Learning Experiences on a Global Scale (Vol. 4753, pp. 158-171). Heidelberg: Springer. Retrieved fromhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75195-3_12

Kraiger, K. (2008). Transforming Our Models of Learning and Development: Web-Based Instruction as Enabler of Third-Generation Instruction. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(4), 454-467. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.00086.x

Levin, J. (2004) Sociological snapshots 4: seeing social structure and change in everyday life, Sage: Thousands Oaks

Lindstaedt, S., Kump, B., Beham, G., Pammer, V., Ley, T., Dotan, A., & Hoog, R. D. (2010). Providing Varying Degrees of Guidance for Work-Integrated Learning. (M. Wolpers, P. A. Kirschner, M. Scheffel, S. Lindstaedt, & V. Dimitrova, Eds.) Sustaining TEL From Innovation to Learning and Practice 5th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning ECTEL 2010, 6383(6383), 213-228. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16020-2

Lundvall, B. A. (ed.) (1992), National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter

Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning? The case for guided methods of instruction. American Psychologist, 59, 14-19.

Müller-Prothmann, T. (2006). Leveraging Knowledge Communication for Innovation. Framework, Methods and Applications of Social Network Analysis in Research and Development. . Frankfurt Peter Lang.

Nyhan, B., (ed.) (2002) Taking steps towards the knowledge economy reflection on the process of knowledge developments, European Centre for the development of Vocational Training, CEDEFOP.

Nyhan, B. (2002) Capturing the knowledge embedded in practice through action research In: Barry Nyhan (eds) (2001), 111-129.

Perifanou, (forthcoming) Collaborative Blended Learning manual Version 2

Rauner, F. Rasmussen & Corbett (1991) Crossing the Border. The Social and Engineering Design of Computer Integrated Manufacturing System. London: Springer

Rauner, F. (2007): Praktisches Wissen und berufliche Handlungskompetenz Europäische Zeitschrift für Berufsbildung Nr. 40 – 2007/1

Ryberg, T., & Larsen, M. C. (2008). Networked identities: understanding relationships between strong and weak ties in networked environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(2), 103-115.

Schulte, S., Spoettl, G. (2009): Virtual Learning on Building Sites – Didactical and Technological Experiences and Implications. In: Conference Proceedings ICELW 2009. ISBN: 978-0-615-29514-5

Streumer, J. (ed.) (2001). Perspectives on learning at the workplace: Theoretical positions, organisational factors, learning processes and effects. Proceedings Second Conference HRD Research and Practice across Europe, January 26-27, 2001. UFHRD, Euresform, AHRD. Enschede: University of Twente.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G. and Shuen, A. ( 2000) Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management, in: Dosi, G., Nelson, R.R. and S.G. Winter (eds) pp 334 – 379

Toner, P. (2011) Workforce Skills and Innovation: An Overview of major themes in the literature OECD Education Working Paper series. Paris

Vygotsky L.(1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E., White, N., & Smith, J. (2009). Digital Habitats: Stewarding Technology for Communities. Portland, OR: CPSquare

Download the paper here in Word format PLE2012