Microcredentials: a new way of monetarising MOOCs?

geralt (CC0), Pixabay

There is a bit of a buzz going on at the moment around micro credentials. At the European Distance Learning Network (EDEN) annual conference this week, not only did Anthony Camilleri from the European MicroHE project deliver a keynote presentation on micro credentials but there was three follow up sessions based on the work of the projects

Anthony Camilleri says that “HEIs are increasingly confronted with requests from learners to recognize outside learning such as MOOCs as credit towards a degree. For those, students look for the most prestigious and up to date learning opportunities, which they often find online.” He believes the “recognition of micro-credentials can enhance student motivation, responsibility and determination, enabling more effective learning.”

However, it is noted that there remain barriers to the widespread development of micro credentials. These include scaling procedures for the recognition of prior learning, the emergence of parallel systems of credentials and open courses offered by universities do not necessarily award recognised forms of credit.

The MicroHe project is proposing a harmonised European approach to recognizing and transferring open education digital credentials thus enabling virtual student mobility, and “empowering students to adapt their learning portfolio to changing labour market demands and new technological trends.”

A further argument put forward for Microcredentials is that they provide “an alternative approach towards handling the development needs of the modern-day learner, not only helping individual competence development but also offer increased flexibility and personalization.”

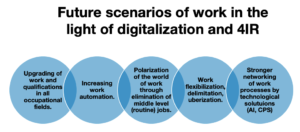

Although the COVID crisis has focused attention on the potential (and possibly, the necessity) of digital course provision a major driver which predates the crisis is the speed of development of automation and AI. There are different predictions of the impact on jobs and perhaps more importantly the tasks with jobs. This diagramme is from a forthcoming publication produced for the Taccle AI project.

But, however it plays out, it seems likely that there will be a need for retraining or upskilling for a significant number of people, and also that there will be increasing demand for highly skilled workers. Microcredentials may well be part of the answer to this need and universities could have a key role in providing online education and training.

However, the question of who pays will be critical. It is interesting that FurtureLearn, the MOOC consortium led by the UK Open University, is getting in on the action. Previously attempts to monetarize their MOOCs has been through charging a fee for certification or extended access to content. But in a email circular this week they announced a new MOOC, run in conjunction with Tableau.

In the age of analytics, transforming large datasets into meaningful customer value is essential to effective data-driven business practice” they say.

“On our new microcredential, Data Analytics for Business with Tableau, starting 13 July, you’ll develop the in-demand data analytics skills you need to progress in your field as a business or data analyst.” The course lasts twelve weeks and is certified by the University of Coventry. It is targeted at early-stage or aspiring data or business analyst, business professional and business or arts graduates looking to start their first professional role. And the cost: 584 Euro for a twelve-week online programme. The course looks very good and the model of micro credentialing could well work. But the cost is likely to be prohibitive for many people, unless, of course there is funding for individuals doing such courses.

which are divided into individual “acts”. In all Sonic games, rings are collected, which the main character loses when touching an opponent. If he is hit without rings, you lose an extra life. In the classic main games, after using up all extra lives and continues, you have to start all over again after a game over.

which are divided into individual “acts”. In all Sonic games, rings are collected, which the main character loses when touching an opponent. If he is hit without rings, you lose an extra life. In the classic main games, after using up all extra lives and continues, you have to start all over again after a game over.