Reflections on the impact of the Learning Layers project – Part Three: The use of Learning Toolbox in new contexts

With my two latest posts I have started a series of blogs that report on the discussions of former partners of the Learning Layers (LL) project on the impact of our work. As I have told earlier, the discussion started, when I published a blog post on the use of Learning Toolbox (LTB) in the training centre Bau-ABC to support independent learning while the centre is closed. This triggered a discussion, how the digital toolset Learning Toolbox – a key result from our EU-funded R&D project – is being used in other contexts. And – as I also told earlier – this gave rise to the initiative of the leader of the Learning Layers consortium to collect such experiences and to start a joint reflection on the impact of our work. In the first post I gave an overview of this process of preparing a joint paper. In the second post I presented the main points that I and my co-author Gilbert Peffer presented on the use of LTB to support vocational and workplace-based learning in the construction sector. In this post I try to give insights into the use of LTB in other contexts based on spin-off innovations and on refocusing the use of the toolset. Firstly I will focus on the development of ePosters (powered by LTB) in different conferences. Secondly I will give a brief picture on the use of LTB for knowledge sharing in the healthcare sector.

Insights into the development of ePosters powered by LTB

Here I do not wish to repeat the picture of the evolution of the ePosters – as a spin-off innovation of the LTB as it has been delivered by the responsible co-authors. Instead, I try to give firstly my impressions of the initial phase of this innovative use of LTB to support poster presenters in conferences. Then, I will give a glimpse, how we tried to present the ePoster approach to the European Conference on Educational Research and to the VETNET network. Here I can refer to my blog posts of that time. Then I will add some information on the current phase of developing the work with ePosters – as presented by the responsible authors for the joint paper on the impact of LL tools.

- In October 2017 I became familiar with the breakthrough experience that the developers of the LTB and the coordinator of the healthcare pilot of the LL project had had with the development of ePosters for conferences. In the annual conference of medical educators (AMEE 2017) they had introduced the ePosters (prepared as LTB stacks) as alternatives for traditional paper posters and for expensive digital posters. At that time I published an introductory blog post – mainly based on their texts and pictures. Foe me, this was a great start to be followed by others. Especially the use of poster cubicles to present mini-posters that provided links to the full ePosters was very impressive. Another interesting format was the use of ePosters attached to Round Tables or Poster Arenas was interesting.

- In the year 2018 we from ITB together with the LTB-developers and with the coordinator of the VETNET network took the initiative to bring the use of ePosters into the European Conference on Educational Research 2018 in Bolzano/ Bozen, Italy. We initiated a network project of the VETNET network (for research in vocational education and training) to serve as a pioneering showcase for the entire ECER community. In this context we invited all poster presenters of the VETNET program to prepare ePosters and the LTB-developers provided instructions and tutoring for them. Finally, at the conference, we had the ePoster session and a special session to e approach for other networks. This process was documented by two blog posts – on September 2nd and on September 11th – and by a detailed report for the European Educational Reseaarch Association. The LTB-stacks stacks for the ePosters can be found here, below you have screenshots of the respective web page.

- In the light of the above the picture that the promoters of ePosters have presented now is amazing. The first pilot was with a large, international medical education conference in 2017. In 2018 it was used at 6 conferences across Europe. In 2019 this number grew to 14 and also included US conferences. The forecast for 2020 is that it will be used by more than 30 conferences with growth in the US being particularly strong. The feedback from users and the number of returning customers suggest that the solution is valued by the stakeholders.

Insights into the use of LTB in the healthcare sector

Here I am relying on the information that has been provided by the coordinator of the healthcare pilot of the Learning Layers and by the former partners from the healthcare sector. Therefore, I do not want to go into details. However, it is interesting to see, how the use of LTB has been repurposed to support knowledge sharing between the healthcare services across a wide region. This is what the colleagues have told us of the use of LTB:

“LTB has been used to create stacks for each practice and thereby improve the accessibility of the practice reports as well as to enable the sharing of additional resources which could not be included in the main report due to space. The app has thus improved the range of information that can be shared, and links are also shared which allow users to read more in-depth into the topic areas. The use of LTB has also enabled the spread of information more widely, as the team suggested that the stack poster (a paper-based poster displaying the link to the stack and a QR code) should be displayed in the practice to allow any interested staff to access the stack and resources. The use of the stack also allows for all the information to be kept by interested staff in one central place, so previous reports and resources can be referred back to at any point. It can also be accessed via a personal mobile device, so gives the opportunity for users to access the information at the most convenient time for them, and without the need to have the paper report or to log in to a system.”

—

I guess this is enough of the parallel developments in using the LTB after the end of the LL project and alongside the follow-up in the construction sector. In the final post of this series I will discuss some points that have supported the sustainability of the innovation and contributed to the wider use of the LTB.

More blogs to come …

Regular readers will know I am working on a project on AI and Vocational Education and Training (VET). We are looking both at the impact of AI and automation on work and occupations and the use of AI for teaching and learning. Later in the year we will be organizing a MOOC around this: at the moment we are undertaking interviews with teachers, trainers , managers and developers (among others) in Italy, Greece, Lithuania, Germany and the UK.

Regular readers will know I am working on a project on AI and Vocational Education and Training (VET). We are looking both at the impact of AI and automation on work and occupations and the use of AI for teaching and learning. Later in the year we will be organizing a MOOC around this: at the moment we are undertaking interviews with teachers, trainers , managers and developers (among others) in Italy, Greece, Lithuania, Germany and the UK.

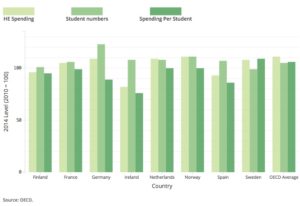

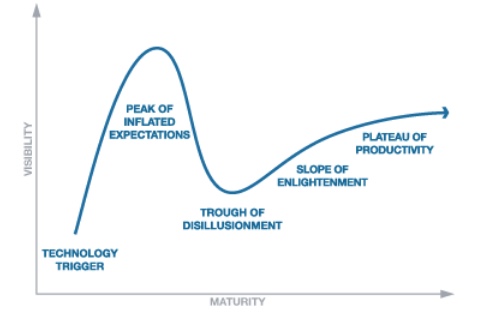

In this brave new data world, we seem to get daily reports on the latest statistics about education. It si not easy making sense of it all.

In this brave new data world, we seem to get daily reports on the latest statistics about education. It si not easy making sense of it all. Has Learning Analytics dropped of the peak of inflated expectations in Gartner’s hype cycle? According to Educause ‘Understanding the power of data’ is still there as a major trend in higher education and Ed Tech reports a

Has Learning Analytics dropped of the peak of inflated expectations in Gartner’s hype cycle? According to Educause ‘Understanding the power of data’ is still there as a major trend in higher education and Ed Tech reports a