geralt (CC0), Pixabay

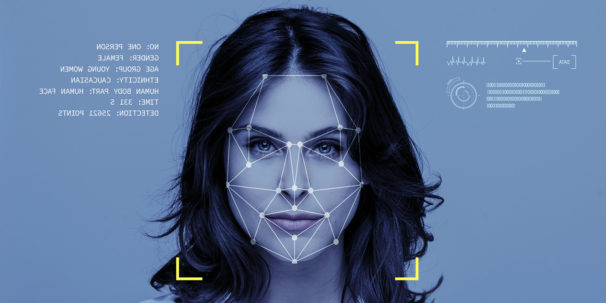

The news that IBM is pulling out of the facial recognition market and is calling for “a national dialogue” on the technology’s use in law enforcement has highlighted the ethical concerns around AI powered technology. But the issue is not just confined to policing: it is also a growing concern in education. This post is based on a section in a forthcoming publication on the use of Artificial Intelligence in Vocational Education and Training, produced by the Taccle AI Erasmus Plus project.

Much concern has been expressed over the dangers and ethics of Artificial Intelligence both in general and specifically in education.

The European Commission (2020) has raised the following general issues (Naughton, 2020):

- human agency and oversight

- privacy and governance,

- diversity,

- non-discrimination and fairness,

- societal wellbeing,

- accountability,

- transparency,

- trustworthiness

However, John Naughton (2020), a technology journalist from the UK Open University, says “the discourse is invariably three parts generalities, two parts virtue-signalling.” He points to the work of David Spiegelhalter, an eminent Cambridge statistician and former president of the Royal Statistical Society who in January 2020 published an article in the Harvard Data Science Review on the question “Should we trust algorithms?” saying that it is trustworthiness rather than trust we should be focusing on. He suggests a set of seven questions one should ask about any algorithm.

- Is it any good when tried in new parts of the real world?

- Would something simpler, and more transparent and robust, be just as good?

- Could I explain how it works (in general) to anyone who is interested?

- Could I explain to an individual how it reached its conclusion in their particular case?

- Does it know when it is on shaky ground, and can it acknowledge uncertainty?

- Do people use it appropriately, with the right level of scepticism?

- Does it actually help in practice?

Many of the concerns around the use of AI in education have already been aired in research around Learning Analytics. These include issues of bias, transparency and data ownership. They also include problematic questions around whether or not it is ethical that students should be told whether they are falling behind or indeed ahead in their work and surveillance of students.

The EU working group on AI in Education has identified the following issues:

- AI can easily scale up and automate bad pedagogical practices

- AI may generate stereotyped models of students profiles and behaviours and automatic grading

- Need for big data on student learning (privacy, security and ownership of data are crucial)

- Skills for AI and implications of AI for systems requirements

- Need for policy makers to understand the basics of ethical AI.

Furthermore, it has been noted that AI for education is a spillover from other areas and not purpose built for education. Experts tend to be concentrated in the private sector and may not be sufficiently aware of the requirements in the education sector.

A further and even more troubling concern is the increasing influence and lobbying of large, often multinational, technology companies who are attempting to ‘disrupt’ public education systems. Audrey Waters (2019), who is publishing a book on the history of “teaching machines”, says her concern “is not that “artificial intelligence” will in fact surpass what humans can think or do; not that it will enhance what humans can know; but rather that humans — intellectually, emotionally, occupationally — will be reduced to machines.” “Perhaps nothing,” she says, “has become quite as naturalized in education technology circles as stories about the inevitability of technology, about technology as salvation. She quotes the historian Robert Gordon who asserts that new technologies are incremental changes rather than whole-scale alterations to society we saw a century ago. Many new digital technologies, Gordon argues, are consumer technologies, and these will not — despite all the stories we hear – necessarily restructure our world.

There has been considerable debate and unease around the AI based “Smart Classroom Behaviour Management System” in use in schools in China since 2017. The system uses technology to monitor students’ facial expressions, scanning learners every 30 seconds and determining if they are happy, confused, angry, surprised, fearful or disgusted. It provides real time feedback to teachers about what emotions learners are experiencing. Facial monitoring systems are also being used in the USA. Some commentators have likened these systems to digital surveillance.

A publication entitled “Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education- where are the educators?” (Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Victoria I. Marín, Melissa Bond & Franziska Gouverneur (2019) which reviewed 146 out of 2656 identified publications concluded that there was a lack of critical reflection on risks and challenges. Furthermore, there was a weak connection to pedagogical theories and a need for an exploration of ethical and educational approaches. Martin Weller (2020) says educational technologists are increasingly questioning the impacts of technology on learner and scholarly practice, as well as the long-term implications for education in general. Neil Selwyn (2014) says “the notion of a contemporary educational landscape infused with digital data raises the need for detailed inquiry and critique.”

Martin Weller (2020) is concerned at “the invasive uses of technologies, many of which are co-opted into education, which highlights the importance of developing an understanding of how data is used.”

Audrey Watters (2018) has compiled a list of the nefarious social and political uses or connections of educational technology, either technology designed for education specifically or co-opted into educational purposes. She draws particular attention to the use of AI to de-professionalise teachers. And Mike Caulfield (2016) in acknowledging the positive impact of the web and related technologies argues that “to do justice to the possibilities means we must take the downsides of these environments seriously and address them.”

References

Caulfield, M. (2016). Announcing the digital polarization initiative, an open pedagogy project [Blog post]. Hapgood. Retrieved from https://hapgood.us/2016/12/07/announcing-the-digital-polarization-initiative-an-open-pedagogy-joint/

European Commission (2020). White Paper on Artificial Intelligence – A European approach to excellence and trust. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Gordon, R. J. (2016). The Rise and Fall of American Growth – The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War. Princeton University Press.

Naughton, J. (2020). The real test of an AI machine is when it can admit to not knowing something. Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/22/test-of-ai-is-when-machine-can-admit-to-not-knowing-something.

Spiegelhalter, D. (2020). Should We Trust Algorithms? Harvard Data Science Review. Retrieved from https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/56lnenzj, 27.02.2020.

Watters, A. (2019). Ed-Tech Agitprop. Retrieved from http://hackeducation.com/2019/11/28/ed-tech-agitprop, 27.02.2020

Weller, M (2020). 25 years of Ed Tech. Athabasca University: AU Press.

As part of the Taccle AI project, around the impact of AI on vocational education and training in Europe, we have undertaken interviews with managers, teachers, trainers and developers in five European countries (the report of the interviews, and of an accompanying literature review, will be published next week). One of the interviews I made was with

As part of the Taccle AI project, around the impact of AI on vocational education and training in Europe, we have undertaken interviews with managers, teachers, trainers and developers in five European countries (the report of the interviews, and of an accompanying literature review, will be published next week). One of the interviews I made was with